How the simple fork almost tore apart the fabric of society

The fork’s journey from reviled symbol of moral decay to utilitarian instrument is a story of power, privilege, and humanity’s relentless desire to control and refine.

The dinner fork is one of the most common fixtures at tables worldwide—so ordinary, so unthreatening, that few give it a second thought. But for centuries, the fork was condemned as a symbol of decadence, moral decay, and social arrogance.

Throughout most of history, fingers were nature’s utensils. Knives sliced meat, spoons scooped broth, but only the hand completed the act of nourishment. The fork, however, was something else entirely. “The introduction of the fork reflected and, at the same time, accelerated a series of profound changes in food culture and table habits,” says Lucia Galasso, a food anthropologist from Rome. It brought about a more controlled, refined eating process—one that not everyone welcomed.

The fork’s journey from forbidden instrument to universal utensil reveals how even the simplest objects can wield immense cultural power. From its controversial debut in Byzantine courts to its notable association with Italian elite during the 16th century, the fork sparked a wave of scandal, rejection, and fear of change. Its introduction was not just a matter of culinary innovation, but a significant cultural shift with enduring impacts on social interactions and dining rituals that sparked ongoing debates about what it truly means to be civilized.

The pre-prong era

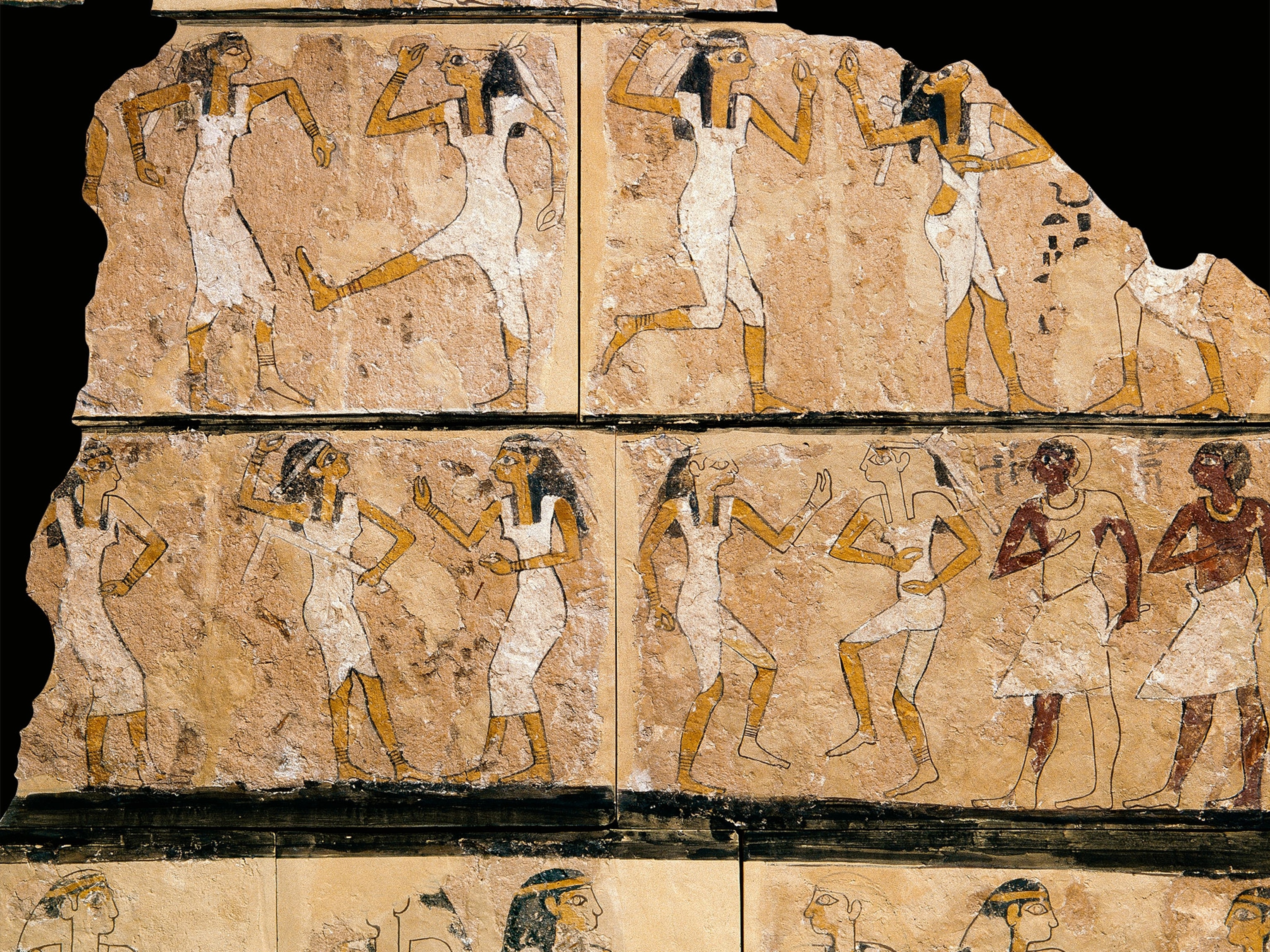

Archaeological evidence suggests that fork-like tools existed in ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome, but they were primarily used for cooking and serving, not for personal eating. Roman banquets, for example, often featured elaborate silverware, yet diners still used their hands for most foods, occasionally employing knives or spoons.

(Is that an ancient pizza? Here’s what people really ate in Pompeii.)

“For millennia, man used his fingers to bring food to his mouth,” explains Galasso. “It was probably for this reason that the need for a fork was felt less than that of the spoon and knife; in fact, it was born last, and its use was sporadic before its definitive adoption towards the middle of the 19th century.”

This preference for hand-eating wasn’t just practical, but cultural. Across Europe, communal eating from shared platters was common. Hands and knives were used to tear and share food, reinforcing a sense of closeness and shared experience at the table.

The fork's resemblance to the devil’s tines

The first major scandal involving the fork took place in the 11th century when Princess Maria Argyropoula, a Byzantine noblewoman, married the Venetian Doge’s son. At her lavish wedding feast, Maria produced an ornate, two-pronged golden fork and used it to bring food to her lips.

Shortly after the event, a Venetian clergyman publicly condemned her actions in a passionate sermon. “God in his wisdom has provided man with natural forks—his fingers,” he declared. “Therefore, it is an insult to Him to substitute them with metal forks.”

For the clergy, the fork wasn’t just unnecessary—it was an affront to the divine order. Hands were how people were meant to eat, just as Christ and his disciples had at The Last Supper. Inserting a man-made tool between hand and mouth disrupted a sacred, natural act.

The fork’s rise amongst the upper class during the 11th century left a bad taste in the mouths of religious leaders and cultural purists. The clergy feared it signified a dangerous shift in how society controlled food, power, and behavior.

Religious leaders also couldn’t ignore the fork’s disturbing resemblance to the devil’s pitchfork. At a time when Satan was frequently depicted holding a three- or four-pronged trident, the fork felt too close for comfort.

(The hellish history of the devil: Satan in the Middle Ages.)

According to Galasso, the Church’s resistance to the fork also reflected deeper fears about wealth, indulgence, and moral decay. “The Church preached simplicity at the table,” she explains. “Hands were seen as a direct, humble connection to food—something that all people, rich or poor, shared. The fork, by contrast, was an emblem of excess, a sign of aristocratic vanity.”

Before the fork, dining was all about getting your hands dirty—literally. “Medieval tables were chaotic, but structured by social negotiation,” says Albala. “You reached into shared dishes, carved off what you needed, and physically connected with both the food and the people around you. Dining was intimate; you literally touched the same food as your companions.” Even royalty embraced this hands-on approach, sharing directly from common plates and oversized platters, reinforcing bonds through the messy, primal act of eating.

But when the fork arrived, it carved a sharp divide at the table. Food was no longer something shared warmly by hand; it became something to be pierced, controlled, and manipulated. The fork’s prongs didn’t just stab at food, but also tradition. And, for the wealthy and powerful, that was precisely the point. Europe’s aristocrats and wealthy merchants quickly embraced the fork’s novelty, prizing its sophistication and using it to draw a line between the refined and the five-fingered faithful.

The rise of the fork amongst Europe artistocrats

Despite efforts to skewer its reputation, the fork firmly planted itself at the table of high society, amongst Europe’s elite. Its status as an aristocratic symbol only fed resentment from clergy and commoners alike.

Renaissance Italy's aristocratic circles embraced the fork earlier than other European regions, largely due to their exposure to the refined utensil practices from Byzantine and Arab cultures. Italian cuisine itself was evolving toward dishes that required more precise and delicate handling. Dishes like slippery pasta noodles, elaborate meat preparations, fruits preserved in syrup, and sugared delicacies became increasingly fashionable, making forks not just convenient but practically indispensable. The fork facilitated a shift away from dishes that favored drier consistencies and fewer sauces, directly influencing culinary practices and plating techniques.

(The twisted history of pasta.)

This culinary evolution paralleled broader cultural shifts, contributing to a more structured, formal dining experience. "[The fork] signaled distance from what was considered a basic animal act: eating,” Albala says. “It created individual boundaries around diners, reflecting a deeper cultural shift towards formality, personal space, and self-control."

One figure pivotal to the fork’s spread is Catherine de’ Medici, born into the influential Florentine Medici family. When she married Henry II of France in 1533, Catherine did not simply transplant Italian cuisine to France; she also introduced an elaborate set of table manners, etiquette, and cutlery customs that prominently featured the fork. As Galasso points out, although forks had already begun appearing among French aristocrats, Catherine’s presence validated and popularized their usage. Her lavish banquets and emphasis on refined manners transformed the utensil from a curious novelty into a definitive symbol of elegance, refinement, and social distinction in French aristocratic circles.

Even with noble endorsement, the fork’s acceptance was slow and uneven. In England and early America, men particularly resisted it. Forks were often seen as unmanly—an unnecessary affectation that separated diners from the real, physical act of eating. “When Henry III of France used a fork, people mocked him, saying, ‘Of course you use a fork, you dress like a lady,’” Albala says.

But as nobles increasingly demanded individual plates, cups, and utensils, the fork became more than a piece of cutlery. It became a status symbol and an instrument of exclusion to elevate the wealthy, distance the devout, and separate the refined from the unrefined.

“The fork didn’t just change how we eat,” explains Albala. “It changed who we are at the table, how we interact with each other, and how we think about food itself. It was a tool of separation—separating people from their food, from each other, and from their most basic instincts.”

Where the fork stands today

The fork spread beyond elite circles in the late 17th and 18th centuries due to increased trade, globalization, and the emergence of individual place settings. By the 19th century, forks were standard utensils across Europe and parts of America, particularly in France and England, where dining etiquette became highly formalized.

Even as forks entered everyday use, rituals around their handling continued to influence culinary culture. Victorian-era dining, for instance, emphasized precise fork-and-knife etiquette, inspiring detailed etiquette guides. But as mass production made utensils affordable to broader populations, the fork’s aristocratic allure diminished.

Ironically, the fork’s refined image is now what contributes to its decline. “The idea that you must use a fork in a certain way is fading, just like the strict dining etiquette of the Victorian era,” Albala notes.

Today’s culinary landscape is circling back to what the fork once sought to eliminate: tactile engagement with food, the joy of sharing, and the primal pleasure of eating with one’s hands. Street cuisine and communal dining are gaining popularity by highlighting direct, sensory interactions with food.

“A third of the world still eats with their hands,” says Galasso. “And in many cases, Westerners are rediscovering the intimacy and connection hand-eating provides.”

The fork may have subdued our animal instincts, but our insatiable appetite for connection remains. After all, the act of eating has always been a universal language, one that no single tool can ever fully control.