Copper price to surge to record high this year, Trafigura forecasts

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Copper prices will surge to a record high this year as a rebound in Chinese demand risks depleting already low stockpiles, the world’s largest private metals trader has forecast.

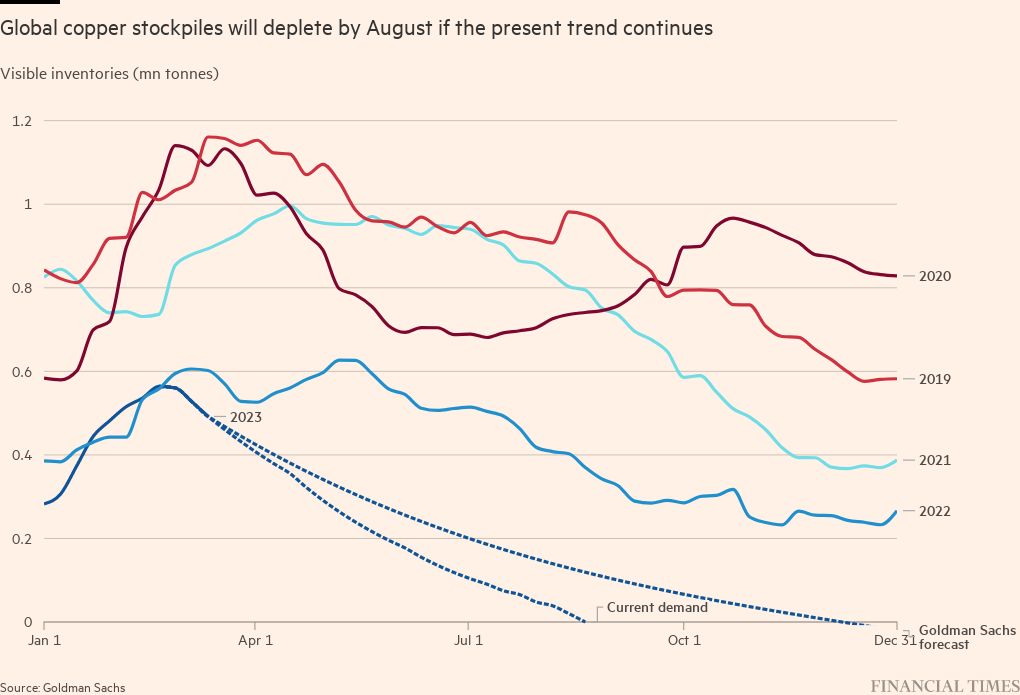

Global inventories of the metal used in everything from power cables and electric cars to buildings have dropped rapidly in recent weeks to their lowest seasonal level since 2008, leaving little buffer if demand in China continues to pace ahead.

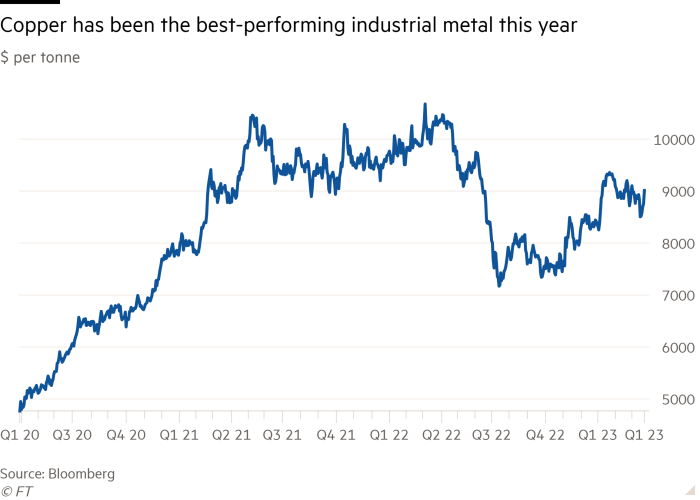

The benchmark three-month copper contract is trading at $9,000 a tonne, having gained 30 per cent since falling sharply in the three months after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine when investors fretted that soaring energy prices would dent metals demand.

Kostas Bintas, co-head of metals and minerals at Trafigura, the Singapore-based trading house, said that copper prices would probably surpass the $10,845 a tonne peak achieved in March 2022 and could even hit $12,000 a tonne.

“I think it’s very likely in the next 12 months that we will see a new high,” Bintas said at the FT Commodity Global Summit in Lausanne, Switzerland. “What’s the price of something the whole world needs but we don’t have any of?”

Goldman Sachs expects the world to run out of visible copper inventories by the third quarter of this year if demand in China continues to power ahead as strongly as it did in February.

Chinese copper demand was up 13 per cent year on year last month, according to the bank, after activity picked up after the lunar new year, which took place earlier this year than last. It forecasts that copper could hit $10,500 a tonne in the near-term, before reaching $15,000 by 2025.

“The forward outlook is extraordinarily positive,” said Jeffrey Currie, global head of commodities research at Goldman Sachs.

He added that “like oil in the 2000s, you’ve got to absolutely love copper in the 2020s”, referring to the 5 per cent supply-demand gap that led Brent crude to rally from $20 to almost $150 a barrel versus an expected 15 per cent deficit for copper this decade.

Copper has been the best-performing industrial metal this year, gaining 6 per cent while others such as zinc and nickel have fallen on broader financial market weakness.

Despite that, several strategists and traders said that prices of commodities were failing to reflect sufficiently market expectations of supply deficits.

Guillaume de Dardel, head of energy transition metals at Mercuria, a Swiss-based trader, said that current prices “don’t fully reflect the anticipation of supply and demand shocks in the future” and commodities “price the present more than the future”.

Copper is crucial to decarbonisation because the replacement of fossil fuels with renewable power requires vast amounts of the metal to distribute electricity longer distances from diffuse wind and solar farms to households and factories that consume it.

Metals analysts said that demand for copper had accelerated and been pushed higher by clean energy industrial policies in the US and Europe that rely on electrification.

Mining executives say it is increasingly difficult to boost new supply of copper with declining grades. Mining billionaire Robert Friedland told the Financial Times it took him 28 years to develop the vast Kamoa-Kakula mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo, which is ramping up to supply 650,000 tonnes by the end of next year.

“We are heading towards a train wreck,” he said. S&P Global estimates that 40mn tonnes of copper will be consumed a year by 2030, up from 25mn tonnes in 2021.

Depleted inventories can make commodity prices volatile and a sudden price surge can cause problems for producers, traders and consumers in finding enough cash to cover margin requirements and avoiding running into a liquidity crunch.

However, some in the market see reason to expect the copper shortages and price surge to be felt later this decade. BHP, the world’s largest mining company, told the conference that new supply from Peru, Chile and the DRC would keep the market in surplus for the next two to three years.

Marc Bailey, chief executive of Sucden Financial, a London-based commodity brokerage, agreed, saying that he expected a rebuilding of copper stocks this year as lockdowns lifted in China.

“It’s the same way that we reopened our economy, which is that we wanted to look after ourselves and feel good, we wanted to go to restaurants, travel, see friends. We didn’t want to buy houses,” he said.

But others said that copper’s role in decarbonising the economy together with the difficulties in developing new mines meant that prices of the red metal were certain to shoot higher soon.

“You can think of copper almost like being a house in a casino,” said Nick Popovic, joint head of copper and zinc trading at Glencore, referring to the high likelihood of rising prices. “The house always wins no matter what permutation we look at and the bottlenecks.”

Comments